Front Cover

| Language: English |

| No. of Pages: 8 |

| Dimensions: 185mm x 280mm x 1mm |

| Publication Frequency: Weekly |

|

| Item Identification Code (UID#): 938 |

| Shelving Location: Book Leaves |

| Estimated Value: £15.00 |

| Purchase Date: 24 November 2006 |

| Purchased From: Log In to view this |

| Price Paid: Log In to view this |

|

The Penny Magazine

423: November 3, 1838

|

|

|

The Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge (1838).

|

|

Folded Sheets

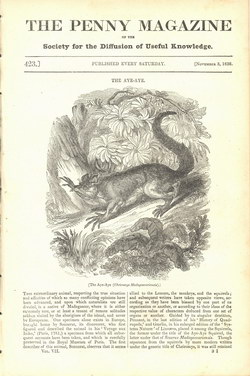

This issue of The Penny Magazine of the The Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge was published in the second year of the reign of Queen Victoria. It contains an early description of the Aye-Aye (then classified as Cheiromys madagascariensis and now as Daubentonia madagascariensis). The article describes the first specimen ever to be brought to Europe and how initially it was widely thought to belong to the rodent order. The front page is illustrated with an engraving depicting an Aye-Aye.

|

Full Text of Article

|

|

This extraordinary animal, respecting the true situation and affinities of which so many conflicting opinions have been advanced, and upon which naturalists are still divided is a native of Madagascar, where it is either extremely rare, or at least a tenant of remote solitudes seldom visited by the aborigines of the island, and never by Europeans. One specimen alone exists in Europe, brought home by Sonnerat, its discoverer, who first figured and described the animal in his 'Voyage aux Indes,' (Paris, 1781,) a specimen from which all subsequent accounts have been taken, and which is carefully preserved in the Royal Museum of Paris. The first describer of this animal, Sonnerat, observes that it seems

allied to the Lemurs, the monkeys, and the squirrels; and subsequent writers have taken opposite views, according as they have been biassed by one part of its organization or another, or according to their ideas of the respective value of characters deduced from one set of organs or another. Guided by its singular dentition, Pennant, in the last edition of his 'History of Quadrupeds,' and Gmelin, in his enlarged edition of the 'Systema Naturæ' of Linnæus, placed it among the Squirrels, the former under the title of the Aye-Aye Squirrel, the latter under that of Sciurus Madagascariensis. Though separated from the squirrels by more modern writers under the generic title of Cheiromys, it was still retained

among the Rodents by many celebrated naturalists, and among them by Cuvier, who, however, was not unaware of its affinity to the Lemurs, and who, after describing its dentition, observes that "its extremities are all furnished with five toes; of those of the anterior, four are excessively long, and of these the middle finger is much more attenuate than the rest; on the hind feet the thumb is opposable to the other toes so that in this respect these animals are, among the rodents, what the opossums are among the carnivora. The structure of the skull, however, is moreover very different from that of other rodents, and has more than one relationship with the Quadrumana." Dr. Fleming and Mr. Swainson, differing as they do in their principles of arrangement, both retain it in the order Rodentia, the latter observing that its affinities are uncertain, but that "the teeth and skull are so decidedly in favour of its belonging to tile glires (rodents), that we prefer for the present to include it in that order." (See 'Cabinet Cyclop.,' Quadrup., p. 90.) M. F. Cuvier, in his work entitled "Des Dents des Mammifères," considers the Aye-Aye as the type of a form intermediate between the Quadrumana and Rodentia, but distinct from either.

On the other hand Schreber regarded it as a Lemur, and described it under the name of Lemur psilodactylus; as did also Linnæus himself who characterizes it as an "ashy ferruginous Lemur, with a bushy tail, and the middle finger of the fore-paws very long and naked." M. Blainville, in a pamphlet recently published, entitled "Sur Quelques Anomalies de Systéme [sic] Dentaire dans les Mammifères," observes that notwithstanding the rodent-like character of its teeth, it is, as is proved by the rest of its organization, as well as by its manners and habits, a true Lemur, having absolutely no relationship with the rodents, no affinity to them, in spite of what many naturalists have imagined. We have ourselves lately had an opportunity of carefully examining this remarkable animal, or rather its preserved remains, in the Museum at Paris, and we do not hesitate to regard it as belonging to the Lemurine family, of which, in the language of some zoologists, it is one of the aberrant forms. The teeth, in certain respects, resemble those of the rodents, consisting only of incisors and molars, an unoccupied space intervening between them. The incisors are two above and two below, strong, powerful, and opposed, is in the rodents; those below are compressed laterally, but deep from before backwards, and extend each in an alveolus carried out in the ramus of the lower jaw throughout its whole extent. They are acutely pointed, their apex resembling a ploughshare They are indeed miniature representations of the huge curved canines in the lower jaw of the Hippopotamus. The upper incisors are not so obliquely pointed, but are also deeper from before backwards than from side to side. The molars are four on each side above, and three below. They are small, rooted, and of simple structure. The head is moderate, rounded, and terminating in a short and rather pointed muzzle; the eyes are very large, and of a nocturnal character; the osseous ring of the orbits is complete; tile ears are large, elongated, subacute at the points, naked within, and thinly strewed externally with longish hairs. Obscure rugæ across their internal aspect seem to denote that, as in the Galagos, they are capable of being folded down, a power possessed also by numerous bats, and among them by the large-eared bat

of our island. Tile similarity indeed of the ears of the Aye-Aye to the Bat was not unnoticed by Sonnerat, who describes them us bat-like, black, and smooth. The fore-paws have each five fingers of which that which takes the place of a thumb is short, and arises beyond the base of the rest; these are long and slender, the middle finger being remarkably attenuate, but exceeded in length by the third or ring finger; the thumb is not opposable, and with the other fingers is furnished with sharp hooked claws. The arms are short in proportion to the posterior extremities. The hind limbs are long as in the Galagos, and the feet are prehensile, being furnished with a true opposable thumb, protected by a flat nail; the rest of the toes are of moderate length and stoutness, but the first is the shortest, and, as in the Lemurs, is armed with a straight pointed claw; the rest have hooked claws. The tail is long and bushy, with coarse black or brownish-black hairs. The general colour of the Aye-Aye is ferruginous brown, passing into yellowish grey on the sides of the head, throat, and belly; the feet are nearly black. Beneath the brown outer coat there is on the back and limbs a fine thick undercoat of soft wool of a pale yellow, which appears more or less through the outer.

Of the habits of the Aye-Aye we know nothing but from the account of M. Sonnerat who kept two of these animals, viz. a male and a female, alive in captivity. It would appear that their habits are nocturnal. By day they see with difficulty, and the eyes, which are of an

ochre colour, resemble those of an owl. Timid, quiet, and inoffensive, they pass the day in sleep, and are not aroused without difficulty; when awake their motions are slow, as those of the Lori, and they have the same fondness for warmth; their thick fur indeed sufficiently proves their impatience of cold, as is the case with the true lemurs also, which, as we know, have the body well protected by soft fur; the more needful, as night (between the temperature of which and that of the day in intertropical countries there is a great difference) is the season of their activity. During the day the Aye-Aye slumbers in its secluded retreat, namely, same hole or cavity in which it conceals itself, and from which on the approach of genial darkness it issues forth in quest of food; as the structure of its teeth indicate, its diet consists of buds, fruits, and other vegetable matters, – to which may be added insects and their larvæ for which it is said to search in the crevices and chinks of the bark of trees, dislodging them by means of its long claw-furnished fingers, and by the same means conveying them to its mouth. The individuals alluded to, which were kept alive by Sonnerat fur about two months, were fed upon boiled rice, which they took up with their long slender fingers, using them much in the same manner as the Chinese use their eating-sticks. Sonnerat remarks, that during the whole of the time these animals lived, he never observed them set up their long bushy tail in the same manner as the squirrel does, but that, on the contrary it was always kept trailing at length. To this observation Buffon in his account of the Aye-Aye expressly adverts. The following remark by Buffon is also worth attention:– Of all the animals," he says, "which have the thumb flattened, the tarsier is that which approaches the nearest to the Aye-Aye; they have this character in common between them: moreover they have the same kind of tail, which is long and covered with hair; both also have the ears naked, straight, and transparent, and a vest of woolly fur immediately covering the skin. There is also some degree of resemblance in the feet, for the tarsier has them very long."

In one respect however (setting aside the character of its dentition) the Aye-Aye differs from the Lemurs, and all other animals of the quadrumanous order:– we allude to the situation of the teats in the female, which are two in number, and ventral instead of being pectoral (or seated on the chest). Of the number of young produced nothing is known, – but we may conclude that they amount at the most to not more than two at a birth, and perhaps only one.

The term Aye-Aye is the native name of this singular animal, and is said to be a resemblance of its voice which is a feeble cry, consisting of two plaintive syllables.

Notwithstanding the length of time that has intervened from the discovery of the Aye-Aye by Sonnerat, to the present day, and visited as the island of Madagascar has been by Europeans, – nay more, notwithstanding the residence of Europeans within its shores, it is somewhat strange that no additional information should have been collected respecting the habits and manners of this animal – that no additional specimens should have been obtained, and that not a single notice of a living individual having been seen or captured should have appeared in the records of science.

NB: The Madagascar Library catalogue includes the full text of this article as its copyright is believed to have expired. Please get in touch if this is not the case.

|

Notes

|

- Printed by William Clowes and Sons, London.

|

Condition of Item

|

|

Very Good. Slightly yellowed. Rather fragile but intact, save for the crease of the fold which is mostly broken causing the pages to be nearly detached.

Refer to the glossary for definitions of terms used to describe the condition of items.

|

Categories

|

|

|

|

BUY FROM AMAZON.COM

Browse 100s More Titles in our Madagascar Book Store

|